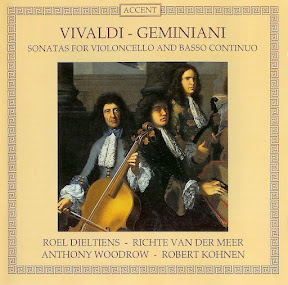

It is now generally accepted that Vivaldi wrote ten cello sonatas – one of them now lost. Six (RV 47, 41, 43, 45, 40 and 46) of the surviving nine were published posthumously as a set, in Paris, by Charles-Nicolas Le Clerc around 1740. The other three survive in manuscript collections: RV 42 (along with RV 46) is preserved in the library at Wiesentheid Castle at Unterfranken in Germany; RV 39 and 44 (along with RV 47) are to be found in a manuscript in the Naples Conservatoire.

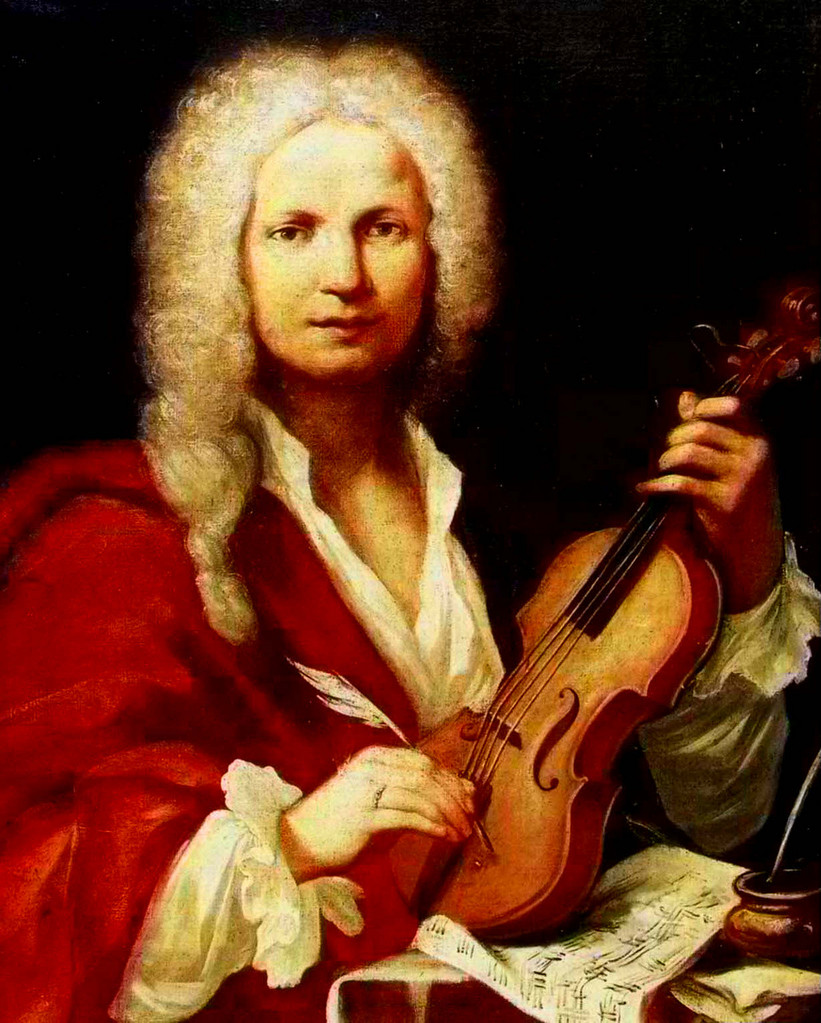

Vivaldi’s sonatas cannot be dated precisely. Without fail they display his profound understanding of the expressive capacities of the instrument. Presumably the lessons he himself learned from his work as teacher of stringed instruments at the Pietà in Venice fed into his writing in these sonatas. All of his nine sonatas are in four movements, disposed slow -fast-slow-fast. In the manuscript of RV 42 the movements carry titles suggesting relationship to particular dances: Preludio-Allemande-Sarabande-Gigue. In the other sonatas the designations are simply of tempos, but the spirit of the dance is never too far away. In his slow movements, Vivaldi’s writing for the cello is often lyrically poignant, but too dignified ever to be merely sentimental.

Vivaldi’s sonatas cannot be dated precisely. Without fail they display his profound understanding of the expressive capacities of the instrument. Presumably the lessons he himself learned from his work as teacher of stringed instruments at the Pietà in Venice fed into his writing in these sonatas. All of his nine sonatas are in four movements, disposed slow -fast-slow-fast. In the manuscript of RV 42 the movements carry titles suggesting relationship to particular dances: Preludio-Allemande-Sarabande-Gigue. In the other sonatas the designations are simply of tempos, but the spirit of the dance is never too far away. In his slow movements, Vivaldi’s writing for the cello is often lyrically poignant, but too dignified ever to be merely sentimental.

Geminiani’s opus 5 consists of six cello sonatas, and was first published in Paris in 1746. His sonatas follow the same basic four movement pattern, though some of his slow movements - such as both the adagio and the grave of Sonata no.6 - are so short that the works are less perfectly balanced as regards tempo. All three of the sonatas played here are full of inventive, but unflashy, writing; the best of the slow movements have a tender melancholy and the closing allegros are delightfully vivacious and witty. Roel Dieltiens’ playing has both the drive and the subtlety displayed in his acclaimed recording (also on Accent) of the Bach suites for solo cello.

I wouldn’t want to make a ‘first choice’ in any of this music. Suffice it to say that Dieltens’ performances are ones to which any listener fond of the baroque cello is likely to make frequent returns. The mixing of sonatas by the two composers is suggestive – though I can’t help wishing that Dieltens had given us a complete recording of one the sonatas by one or other of these two Italian masters.—Glyn Pursglove

Ape, scans

No comments:

Post a Comment